This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue no. 154 of 2006.

MATRIKA (Motherhood and Traditional Resources, Information, Knowledge, and Action) was a three-year p articipatory action research project conducted in collaboration with four local NGOs between 1998 and 2001. Along with NGOs, we researchers conducted workshops for dais, before whom we posed the question: “What does a woman need during pregnancy, birth and postpartum?” The attitudes of our team were crucial to the success of the research work; we used an approach common in counselling, listening actively to what they had to say and encouraging them to speak their own mind instead of sticking to a predetermined questionnaire. We consciously cultivated a team ethos in which we:

articipatory action research project conducted in collaboration with four local NGOs between 1998 and 2001. Along with NGOs, we researchers conducted workshops for dais, before whom we posed the question: “What does a woman need during pregnancy, birth and postpartum?” The attitudes of our team were crucial to the success of the research work; we used an approach common in counselling, listening actively to what they had to say and encouraging them to speak their own mind instead of sticking to a predetermined questionnaire. We consciously cultivated a team ethos in which we:

• Were open to religio-cultural ways of thinking about ‘health’;

• Assumed that poor, illiterate, low caste women could be skilled birth practitioners;1

• Used our capacities for empathy and imagination to enter another world with different ways of understanding the female body;

• Believed that birth is a normal and natural process;

• Understood that apart from pregnancy and birth, poverty is also a factor that compromises women’s health;2 We realised that dais had often been made scapegoats for maternal mortality and morbidity and blamed for the effects of other macro-level processes. Matrika’s workshop methodology reversed the common TBA (Traditional Birth Attendant) training model. We asked groups of dais to ‘train us’ by helping us understand what they thought about and did to meet women’s needs during parturition.

Matrika’s Findings: At first, dais seemed to want to impress us with their knowledge of the modern, biomedical approach. They spoke of the need for using a clean blade, taking the woman to the hospita l if there were problems (when often there are no doctors or hospitals in the area). But as our sincere desire to learn and not ‘teach’ or criticise became apparent — and especially after our own enactments of the loneliness and confusion of a woman going into labour alone in a hospital — they began to trust us and share what they really believed and practised. Ours was a collective effort: a group of researcher-activists interacting with a group of dais. We ate, slept, talked, sang and danced, and produced drawings and plays together. Our workshop activities were a celebration of the dais’ cultural handling of childbirth. We were sometimes told that no one had ever called them together to share and have fun like this.

l if there were problems (when often there are no doctors or hospitals in the area). But as our sincere desire to learn and not ‘teach’ or criticise became apparent — and especially after our own enactments of the loneliness and confusion of a woman going into labour alone in a hospital — they began to trust us and share what they really believed and practised. Ours was a collective effort: a group of researcher-activists interacting with a group of dais. We ate, slept, talked, sang and danced, and produced drawings and plays together. Our workshop activities were a celebration of the dais’ cultural handling of childbirth. We were sometimes told that no one had ever called them together to share and have fun like this.

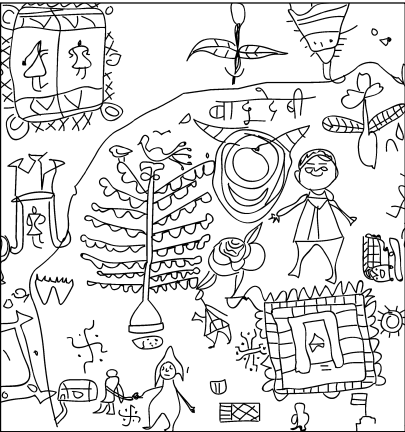

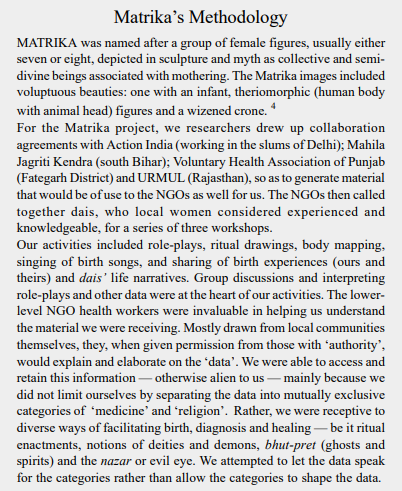

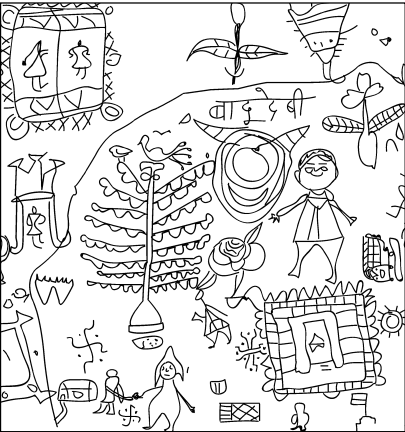

During body mapping sessions, we outlined a woman’s body and then generated terms, often terms of abuse, for parts of women’s bodies. I repeatedly emphasised to our team that we were not generating the equivalent of a bio-medical anatomy chart —rather, we were ‘catching’ women’s stories, their words about and experiences with women’s bodies at the time of pregnancy, birth and postpartum. Motifs from rituals and ritualistic drawings emerged from Rajasthani dais when they were provided with felt pens and large swaths of paper. Note the swastik, or satiyas in the lower left hand corner — a symbol connoting fertility and auspiciousness. Also the sari blouse hung on a tree in the seventh month — the spirit who lives there is evoked to protect the pregnant woman. A Matrika team member drew a poster of Bemata, who dwells in narak, or underground, a visual version of ‘active listening’. Bemata grows both babies in mother’s wombs and plants from the earth. The postpartum “bad” blood is shown here as returning to the earth, completing the cycle. And, in fact, we have heard of families in Delhi’s slums who put sand from the Jamuna river under the charpoy (woven rope cot) to absorb postbirth fluids. This drawing was shown to the dais to make sure we had “got it right”. Notice the ‘three worlds’ (triloka) of heaven (sky), mundane life (earthly plane) and narak (underground). In this way, we were allowing categories like narak to emerge from the data and not producing data to fit into our own researchers’ categories.

How Women Define Narak: The following quotes from our workshop transcripts present meanings of narak. The first series of quotes from Bihar speak explicitly, using the word narak. In other areas, the meanings are more implicit in the practices and the ‘dirtiness’ associated with times of female fertility.

• Girls are considered holy before puberty. The marriage of a young girl, who has not had her periods, is performed with her sitting on her father’s lap. After puberty, the woman is considered unclean, and is unholy, because she bleeds, and this is narak. (Bihar)

• On Chhati (6th) day, the narak period ends. The dai checks if the umbilical cord has fallen off. Then she bathes the baby and beats a thaali (plate). After this, the woman is bathed and wears new clothes. The dai cleans the room where the delivery took place, where the woman was isolated for six days. The dirty clothes of mother and child are washed. After this, the dai is given soap and oil for bathing. All this is on the sixth day after delivery. (Bihar)

Female Body and Earth: It is very tempting for us modern women to frown at ideas of the ‘dirty’ female body and critique them as archaic and misogynist. Having listened carefully to dais’ voices, and having studied Indian, indeed subcontinental representation systems, for almost 30 years, I am now adamantly against doing so.

Although often translated as a hellish or demonic place, narak can be understood as the site or energy of the unseen inner world — of the earth and of the body, particularly the fertile and bleeding female body. Narak has the connotation ‘filth’ but also signifies the fertility or fruitful potential of the earth and women. Socalled ‘pollution taboos’ are related to narak, where the idea of the sacred is radically separated from the reproductive potential of the female body. During menstruation and postbirth, women are ‘unclean’. However, the dai speaks with a very different voice than the pundit about this uncleanness, this narak. She speaks of the placenta, the ultimate polluting substance in the shastra literature, reverently. It is no coincidence that dais are mainly from ‘low’ and ‘outcaste’ communities. Both caste and gender are involved in the concept of narak.

Despite the pejorative connotations of the word narak, the concept has allowed for abiding female spaces and birth cultures. In the ‘male’ or ‘dominant’ view, these female times are ‘filthy’ or polluted, but they are also times when masculine, social and even familial demands on women are suspended. And traditionally, older women guarded these spaces from any incursions — perhaps with the help of ‘demons’ and nether forces!

Within this imagistic representation, the nature of female bodily energy is understood as ‘out of control’ — women are presumed to be more emotional and have special physical needs at this time — so the usual social constraints are suspended. Of course, we need to interrogate the priestly voice and desacralisation of menstruation and birth — but we should not throw out the baby with the bathwater. We should not ignore the traditional birth knowledge of India.

Conversely, the fertility of land and women are acknowledged and honoured. Both are ‘fruitful’ and this is not simply a symbolic device. Within indigenous medical traditions such as Ayurveda, as with the dais, a totally different ontological system is at work. A woman is not a ‘symbol’ of the earth. Nor is the earth a ‘symbol’ of women. Rather, they both partake of the same nature of fecundity. Just as the wind outside my window partakes of the same essence as the breath that flows in and out of my lungs.

During narak time, what is usually closed — the womb — is open, raw, vulnerable and bleeding. Narak allows for the imaging of the unseen and the use of senses other than the visual, as well as the human capacities of empathy and imagination in diagnostics and therapeutics. And, in fact, narak is deeply implicated in the handling of postpartum care.

Postpartum Care: All our workshop area practices — be it ritualistic or regarding indigenous medical systems — were congruent with the concept of narak.

• After delivery, a woman is not given any grain or heavy food. This is called narak fasting. Grain is only given on the third day after all the dirty blood comes out. On the first day, she eats biscuits with tea. She drinks warm water. The second day, heat-producing balls made of ginger, pepper, turmeric, roasted rice, milk and jaggery (saunth laddos) are given. On the third day, rice, dal and vegetables. (Bihar)

• It is called dirty blood because it has collected over nine months in the body. It is dark, smelly and clotted. It comes out first and then fresh clean blood comes out. With a little pressure and massage, we take it out completely and when the colour of the blood becomes clear like during the monthly cycle, we believe that it is clean. (Punjab)

• The gola is baby’s home. When the house becomes empty, only dirty blood is left. When this comes out, there is pain. Hot drinks (of ajwain, saunth, pipar and gur) are given. This drink cleans the belly. After the baby is born, the gola roams around. This gola has taken care of the baby, now it must leave. If the pain is intense, then warm fomentation is done and the gola melts away (pighal jata hai). This is dirty blood and needs cleaning up. (Delhi)

Dais call the postbirth lochia ‘bad blood’ but they do not emphasise the pollution aspect of it. Rather, the blood is ‘bad’ for the mother’s health and needs to come out of the body. Both menstruation and postpartum bleeding are viewed as cleansing the body of ‘toxins’ and this view is congruent with naturopathic and other alternative and indigenous systems of medicine. My working hypothesis is that this blood is called ‘bad’ because if it is retained, it can be bad for the woman’s health. Perhaps in the dominant world religions (Judeo-Christian-Islamic and Hinduism, or more correctly Brahmanism), the concept of narak or ‘hell’ overlays previous meanings that had more to do with the health of women than the purity of priests.

Bidding Goodbye to Bemata: The duration of the period for which the woman is considered ‘unclean’ has been different at different times, even within different religious traditions. Interestingly, both the Leviticus text in the Old Testament of the Bible and the Dharamshastra writings — both of which concern themselves with ritual cleanliness in their respective traditions — specify a longer period of ‘pollution’ for a woman who has given birth to a female infant than a male infant! In the  Indian context, birth is celebrated and the woman’s ‘confinement’ gradually comes to an end.

Indian context, birth is celebrated and the woman’s ‘confinement’ gradually comes to an end.

• On the 13th day after birth, the new mother is allowed to enter the kitchen. (Chauka Charhana). Some do it on the 7th or on the 11th day. Everybody celebrates. There is singing and dancing. On this day, the new mother and the baby bathe and wear new clean clothes. She comes out to get everyone’s blessing. Friends and relatives are invited and eat food together. The dai is given clothes, food and grain. (Punjab)

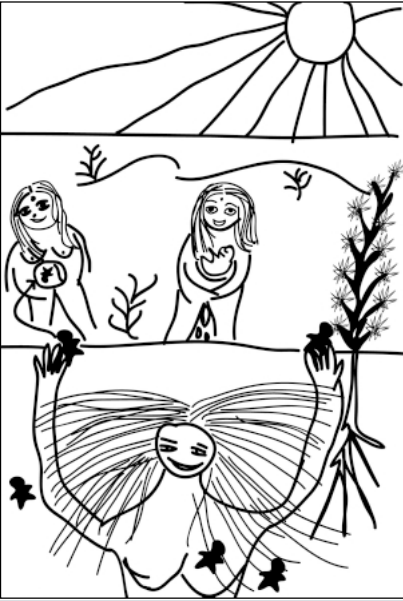

• On the day of the birth ritual celebration (Chhatti), the woman wears everything that was taken off at the time of the birth. She puts on bindi, bangles, henna and nose ring. We make ritual drawings of swastik, worship Bemata and light a lamp. We make a foot impression of the mother on the floor and then the woman enters the main house. Till the 5th day, Bemata roams around the house. After the birth celebrations, Bemata leaves, she goes to another house. The dai also goes to serve others. (Rajasthan) To my knowledge, there are no shrines, formal images or textual references to Bemata. She is definitely a fleeting presence, invoked by women at the time of birth and sent off to another’s home with the postpartum ritual. According to the dais with whom we interacted, Bemata dwells in the realm of narak, deep within the earth. She is a Creatrix responsible for conception, for growth within the womb and birth of human beings as well as the growth of all vegetation. In this image, Bemata was drawn on a charpoy leg along with the swastik, a common post-birth ritual drawing.

Relevance of Bemata: Shakina, a Muslim dai working in a slum of Delhi, talked about birth time in a swirl of Hindu and Muslim references — a testimony to the syncretism of Indian folk culture. We found that Sikh, Christian, Muslim as well as ‘Hindu’ dais used the concepts and often the language of narak and Bemata.

“Look, sister, at the time of birth it’s only the woman’s shakti. She who gives birth, at that time, her one foot is in heaven and the other in hell (narak),”

Shakina goes on to say.

“Before doing a delivery I get the woman to open all the trunks, doors and so on. I pray to the One above to open the knot quickly. I take off her sari, open her hair and take off any bangles or jewellery. I put the atta on a thali and ask the woman to divide it into two equal parts. I also get Rs.1.25 in the name of Sayyid kept separately. But mostly I remember Bemata. Repeatedly, I pray to Bemata, “O mother! Please open the knot quickly.”

Invocations to Islamic and seemingly ‘Hindu’ figures (Bemata) accompany the ‘sympathetic magic’ of opening rituals, the untying of knots, the opening of locks, doors and windows, the loosening of hair and the removal of bangles are all common rites performed during labour throughout North India. This facilitation can be interpreted as an opening in the external word, which is then mimicked or mirrored in the inner world of the maternal body.

The manipulation of the external environment in this way serves as a social permission and encouragement for the ‘opening of the body’. The separation of the atta from one mound into two also imaginatively imitates the separation of the pregnant maternal body into two — mother and baby. When I first encountered these birth facilitations I noticed the parallel in guided imagery used in cancer treatments, when the patient is encouraged to imagine the T-cells and the immune system dealing with tumours. If internal ‘psychic’ imagery could be effective, why should not externally manifest ‘ritual’ imagery also work?

Narak allows for a holistic and non-invasive diagnostics and therapeutics — essentially healthpromoting practices that do not violate the integrity of the body and facilitate the jee or life force. This concept then provides a mode of understanding that allows practitioners and therapeutics to negotiate and influence the inner body without violating the integrity of the skin/body/life force. And indeed, the dais’ health modalities are sophisticated in terms of emotional support and ritual practice as well as practical utilising touch (massage, pressure, manipulation, assisted squat, external version), natural resources (mud, baths and fomentation, herbs, gobar or cow dung), and application of ‘hot and cold’ (in food and drink, fomentation, heating placenta to revive baby, birthing body as ‘heated’ etc.), and isolation and protection (from household work and maternal, familial and sexual obligations.

This interpretation of narak is congruent with some dais’ usage of the terms ‘opening body’ (labour), ‘open body’ (birth) and ‘closing body’ (postpartum) for the entire birthing process. These empirical terms stand in opposition to the factory model of birth (labour, delivery, failure to progress, false labour) implicit in many obstetrical terms. And interestingly, the womb bond between mother and newborn continues to be respected during this time, that is, narak ka samay.

Improving Dai Training: Matrika’s findings about narak have great relevance to public health initiatives targeted at dais. As Matrika data has demonstrated above, dais say, “Bad blood must come out.” However, dai training messages say, “Hemorrhage must stop.” Without referring to dais’ indigenous medical ideas and cultural meanings, dai trainers assume that the dais are ignorant and superstitious — and training effectiveness is therefore compromised.

In the context of postpartum care, narak relates to the ‘bad blood’ that dais think must exit the body. The energy of the maternal body associated with the baby growing is signified by the ‘black blood’ — this fluid emerging denotes not only the uterus contracting but also that the mother’s body is transiting from holding the ‘other’ to releasing the other.

Sometimes we heard that the ‘contractions’ were the womb ‘searching’ for the baby. The dais’ imaging speaks a poetics of the body that attributes consciousness, activity and sensation to the uterus, which is totally absent in the biomedical framework. The understanding and use of these concepts in dai training would significantly improve communications on controlling hemorrhage postpartum while also preserving the respect for indigenous meaning systems.

Furthermore, the Bemata figure encodes a process orientation towards birth and postpartum while providing a framework for diagnostics and therapeutics. In obstetrical practice, the examination done immediately after birth, ‘the Apgar score’, is used to assess the well being of the newborn. It is a scale for measuring the infant’s process of adapting to extra-uterine life. But no such formal, process-oriented assessment is geared towards the bodily functioning of the mother postpartum, the time the dais refer to as ‘the closing of the body’. Bemata seems to function as a diagnostic system assisting dais in their roles as caretakers of mothers, especially crucial in the six-day post-birth period.

More Wholesome Aproach: The practice of not cutting the cord until the placenta is delivered is common in all the areas where Matrika conducted research. Doctors and health workers throughout the country also report it as common practice. Dais have the utmost respect for these parts of the female body usually considered as waste products (by the bio-medical system) or highly polluting (by the Dharamshastras). Dais conceptualise the infant-cordplacenta as a wholesome package. They have been together for nine months, cord and placenta functioning to nurture the foetus — why should they be severed too quickly? Dais say, “Cut the cord after the placenta is delivered.” As mentioned earlier, dais utilise the placenta-cord-newborn connection to revive a listless infant. One dai stated that they had no medicines or machines, so they used what they had — the placenta. But trainers and health education messages throughout the subcontinent are teaching dais to cut the cord right immediately. Interestingly, even midwives in the United States and Europe are questioning the immediate cutting of the cord. We modern, ‘educated’ women have come to believe that ‘pollution’ taboos are atavistic relics of a misogynist and patriarchal past and that they should be superceded by ‘scientific’ understandings of the female body based on fact rather than superstitions. Our Matrika data, gathered by crossing boundaries and listening carefully and respectfully, suggests that dais’ knowledge and practice are encoded in a language, a poetics of the body, which radically differs from that of bio-medical obstetrics, and is more congruent with other Asian medical/health/ healing systems such as Yoga, Ayurveda, Tantra as well as Chinese, Tibetan and even Greek/Islamic medicine.

Need to Crossi Boundaries: In order to facilitate communications in training indigenous midwives, as well as to reclaim aspects of indigenous Indian midwifery that can be used with more privileged women, MATRIKA recommends the development of certain criteria for the evaluation of dais and their practices drawing on Ayurveda and other indigenous systems of health-maintenance and healing. Rather than using the evaluation perspective of biomedicine, indigenous tools of assessment will allow the incorporation of a human resource base that can complement existing ‘reproductive health’ facilities and practitioners. An entire legacy of midwifery knowledge will be erased unless we begin to learn to think and speak the language of narak (and develop daitraining materials dialoguing with that language). Or at the very least, we should not cringe in disdain when we hear or observe women using these languages or observing these practices. Finally, in the Asian subcontinent, it is essential that we begin to include skilled dais in maternal child health programmes at all levels. Hopefully, we will all be able to cross boundaries, listen carefully and help the world to be born more humanely.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This paper was presented at the Conference on Religions and Cultures in the Indic Civilisation organised by CSDS and MANUSHI in December, 2005.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Endnotes

1. For elaboration on the congruence of dais’ knowledge and that of Ayurveda, see “Her One Foot is in this World and One in the Other: Ayurveda, Dais and Maternity” by Anuradha Singh in my edited book Birth and Birthgivers — The power behind the shame (New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications, 2006)

2. Indigenous midwives usually serve the poorest of the poor. Jo Murphy-Lawless provides a clear articulation of the problems for poor, indigenous midwifery practice and practitioners within the context of globalised, technocratic obstetrics in “How Will the World Be Born: The Critical Importance of Indigenous Midwifery” in Royal College of Midwives’ Midwifery Journal, Vol. 6, No. 10 (October, 2003)

3. For an extensive treatment of Bemata and narak in relation to the textual tradition, particularly the Puranas, see my “Negotiating Narak and Writing Destiny: the Theology of Dais’ Handling of Birth” in Invoking Goddesses: Gender Politics in Indian Religion,ed Nilima Chitgopekar (New Delhi: Har-Anand Publishers, 2003)